|

| Ish by Peter H. Reynolds |

When I was younger I would have told you that I wasn't creative. I was never very good at drawing and I have very little musical aptitude so as a child I could only label myself as "not creative." I even had an art teacher who used to fix my work when I was finished to make it more accurate.

I recently had the pleasure to sit and observe an impressive early childhood classroom. I spent most of my observation focused on two boys. One boy was sitting under the climbing structure with a shovel digging "the deepest hole ever," while his companion was filling the dirt from the hole into a red wagon. There was a lot going on in that yard, children coming and going, fighting erupting and resolving but these two little boys kept on digging. They were checking the depth of the hole against their shovel, responsibly collecting the dirt and taking turns when one got tired of his position. At a certain point the digger declared he was 'done' (I presume the center of the earth was getting a little too warm) but the play had only begun. The second had an idea. "Lets get some water."

The mud was delicious. The rich dark liquid coated their hands, shirts, the wagon and even the patio. The boys experimented with the way their new substance flew threw the air, stuck on different objects, and trickled down their arms. "We can build pyramids like in Egypt." one said and then the rock collecting began.

This play continued until the mud hardened, the pyramids had been built (yes, in one day), and the boys were ready for a new adventure.

So you may ask 'is this learning?' 'where was the teacher?' 'what goals did they meet?'

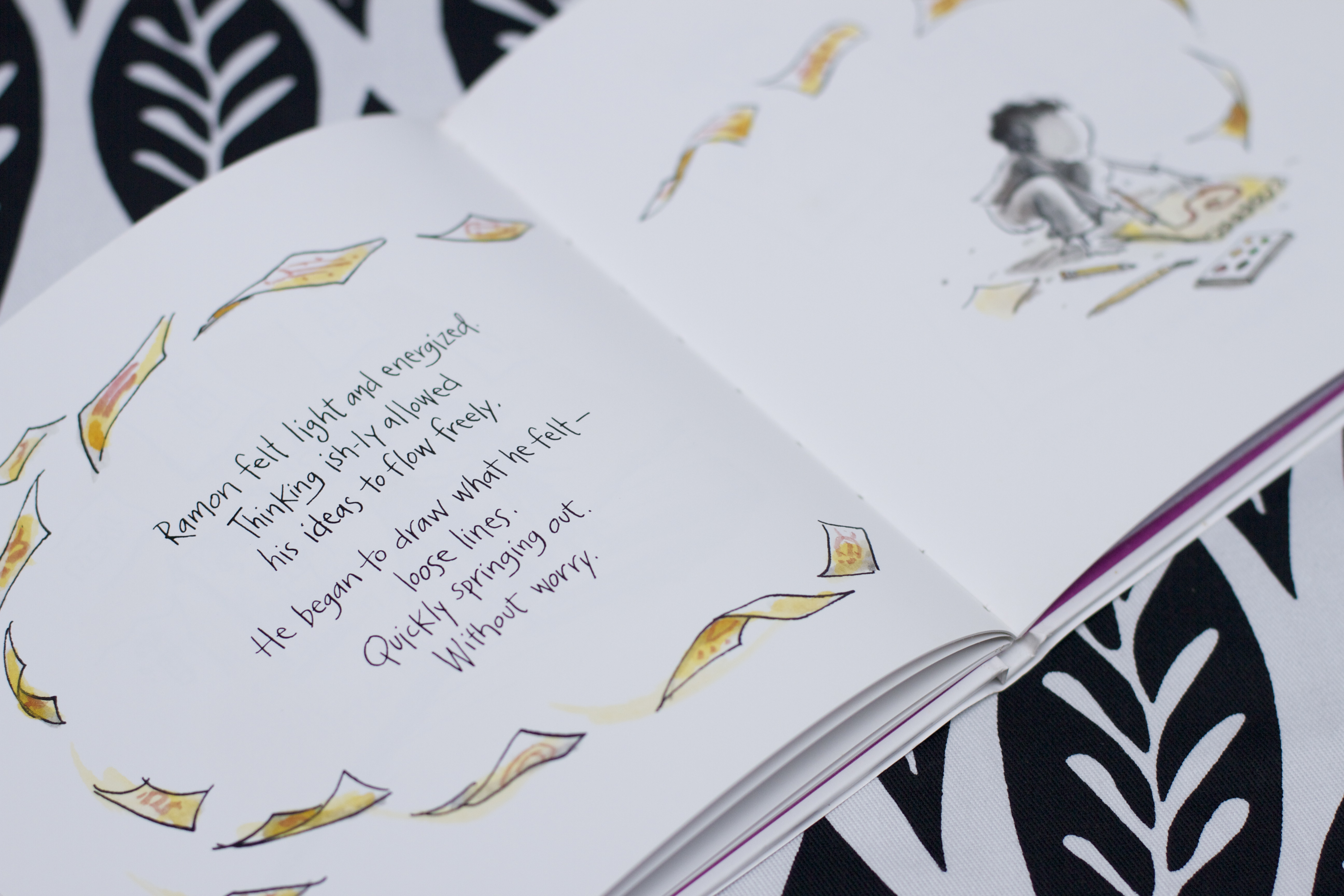

What if I told you they were learning'ish.' There is a wonderful book by Peter H. Reynolds called "Ish." It is about a boy who loved to draw until his brother mocked him for the inaccuracies in his drawings. He gave up drawing all together until his sister points out the "ish" quality of his work. "Ramon felt light and energized. Thinking ish-ly allowed his ideas to flow freely."

No one in this early childhood classroom was worried about the final product. No one cared if the boys were dirty, or there was a hole in the ground, or if there was mud in the wagon. The boys, like most five year olds, were naturally thinking ish-ly and their teachers were going along with it.

Thankfully, this scene is not unique to the school I was visiting. Many early childhood teachers understand the value of "ish" thinking. The products are not what is important, it is truly the process. Students don't need to take home a cute project because they have spent the day really learning and growing. There are a myriad of ways to document student learning and teachers can show this growth through storyboards, videos, anecdotal stories, and photographs.

I can say with confidence that most art teachers don't 'fix' their students' work. Many early childhood teachers understand the value of process over product. But what happens as children grow up? One of my colleagues told me of a course he took on differentiated instruction where the professor lectured the entire time. When asked about his method of teaching the professor replied "there is just too much to cover, I don't have time to differentiate." What happens along the way? How can we go from an open ended mud play to a two hour lecture and expect that each student is really learning the most he can learn? What is the developmentally appropriate way to teach a college age student? Is this a question we even should be asking? Shouldn't students know how to learn on their own by college?

When students enter the workplace they are often put back into the 'ish' zone. Sure they are asked to complete tasks and perform the basics but it really is the 'ish' that will set them apart and lead them to success. It is the out of the box and creative, projects and ideas that make a difference in life. If these students haven't thought 'ish'-ly since they were six, it will be a lot more difficult to switch their thinking at twenty. So how can we make room for the 'ish' in all of our classrooms? How can we reward this thinking and creativity and "allow his ideas to flow freely?"

I won't tell you now that I am not a creative person. It took me years to be able to see the creativity inside myself. I was stuck in the mindset that creativity could only be seen through art or music. Maybe during the poetry unit we did once a year or the creative writing essay that was worth 10 percent of my grade I could use that little bit of creativity I had. But now, as an adult, in real life, I use my creativity every single day. I hope that our students don't have to wait until they are adults to come to this realization. Each and every one of our students should be able to live their lives "ishly ever after" no matter how their creativity manifests itself.